Post by 1dave on Jul 7, 2018 6:28:00 GMT -5

Turquoise Facts:

*Turquoise Thread Transporter*

Basic Information:

Books

The Turquoise Group

Turquoise Facts

Odontolite

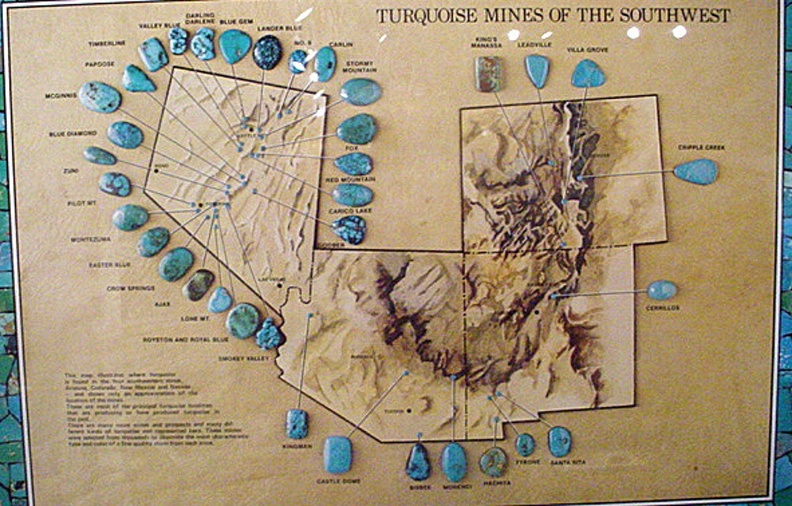

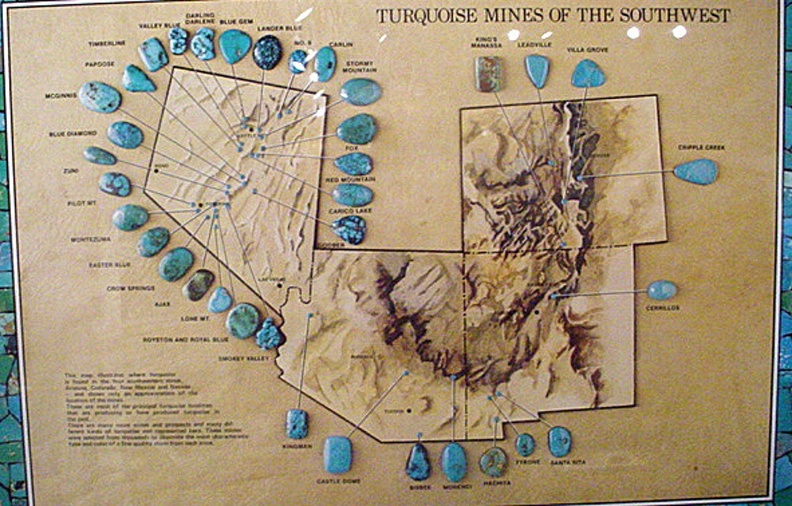

The 4 Top Producing US States:

1. Nevada

Nevada

2. Arizona

3, New Mexico

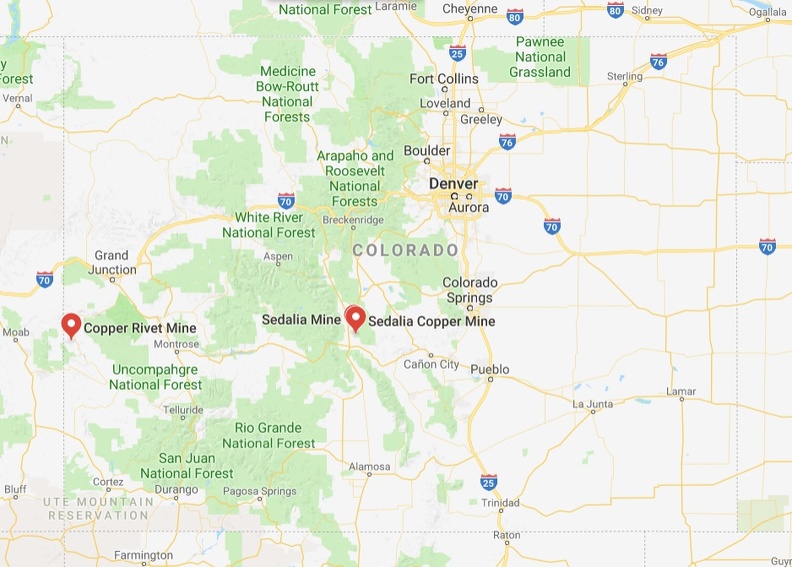

4. Colorado

Other US Locations:

Alabama

Arkansas

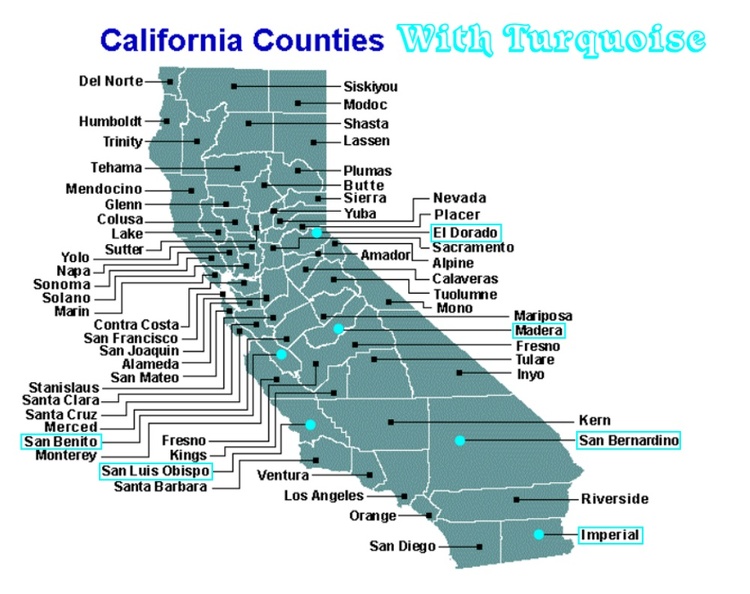

California

Montana

New jersey

North Carolina

Pennsylvania

South Dakota

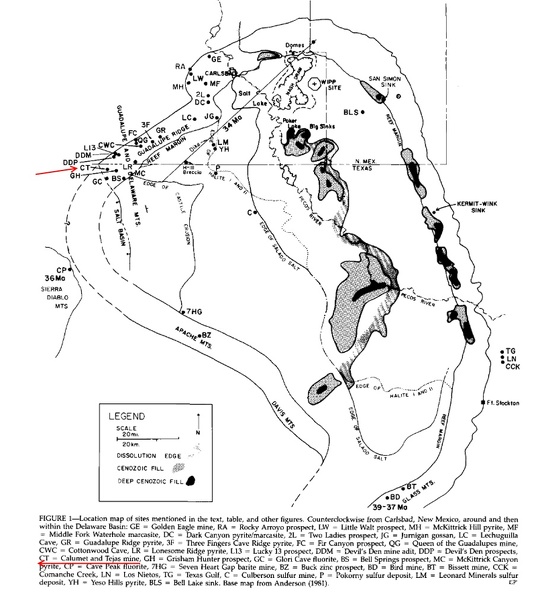

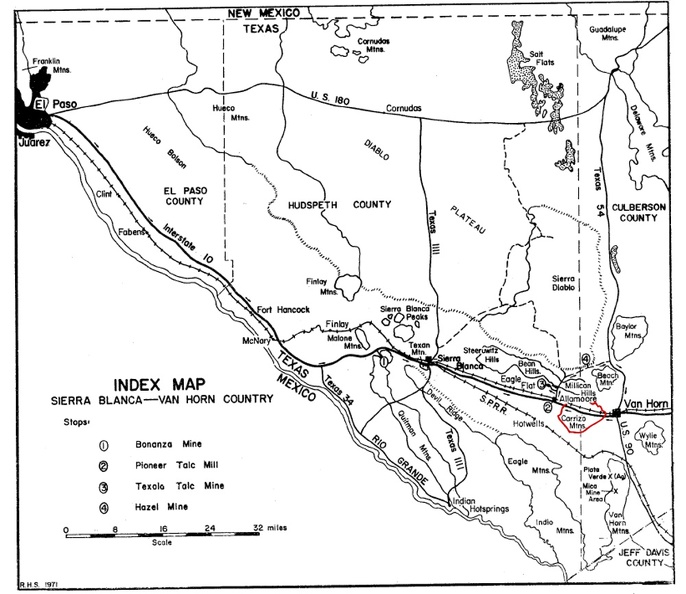

Texas

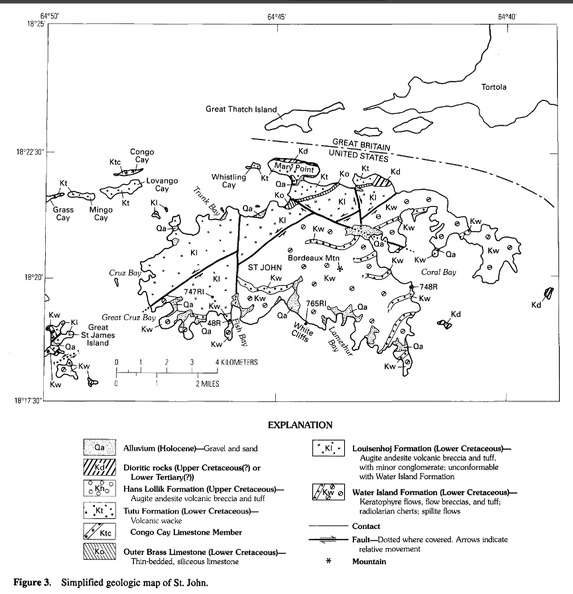

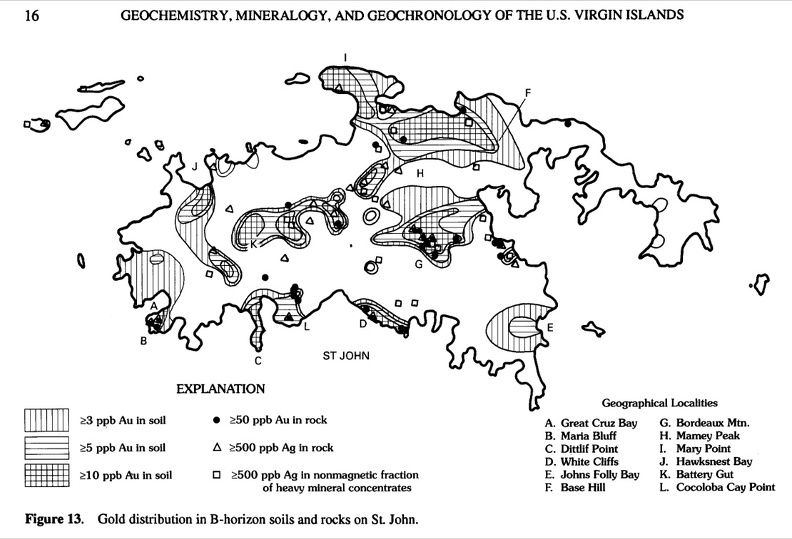

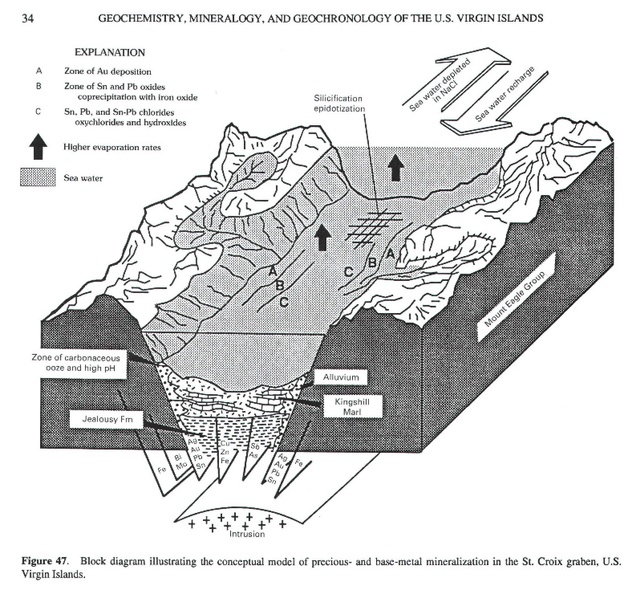

U.S. Virgin Islands

Virginia Turquoise Crystals

Utah

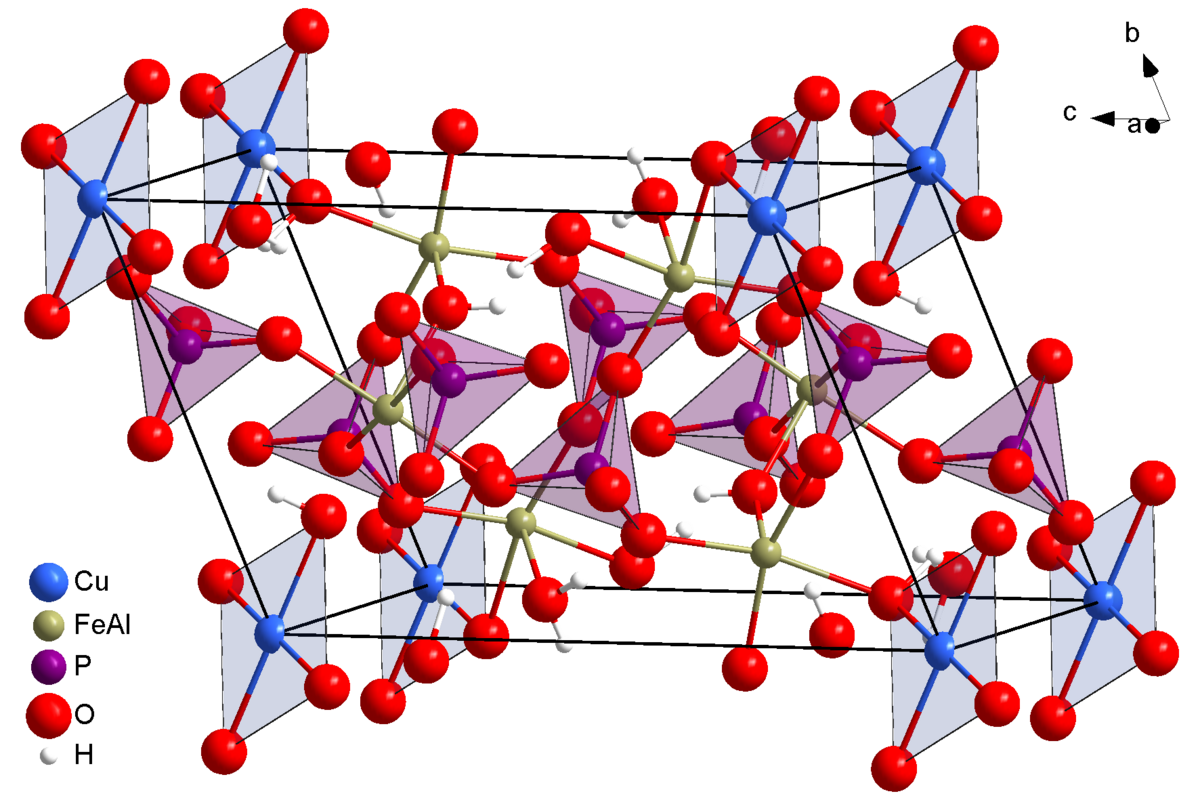

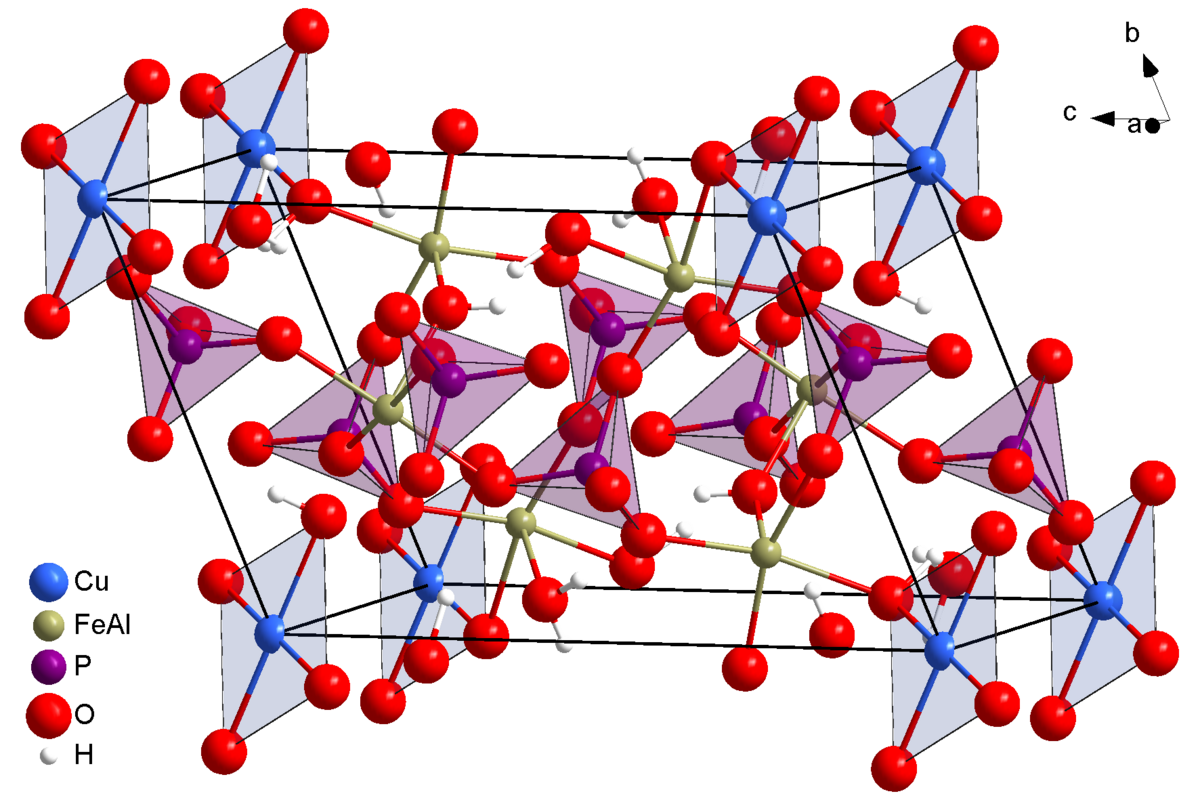

Turquoise Structure

The formation of turquoise requires:

1. Aluminum, the third most common element in the earth's crust after oxygen and silicon

2. Phosphorus, the eleventh most common element

3. Copper, the twenty fifth most common element

and 4. Hot acid to dissolve and re-deposit it as a secondary mineral.

Add a little iron and you get Variquoise.

Add a little zinc and you get Faustite

Remove copper and you get Variscite.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turquoise

The most sought for color is Robin Egg Blue.

Two Excellent sites:

www.durangosilver.com/NevadaturqM.htm

*Turquoise Thread Transporter*

Basic Information:

Books

The Turquoise Group

Turquoise Facts

Odontolite

The 4 Top Producing US States:

1. Nevada

Nevada

2. Arizona

3, New Mexico

4. Colorado

Other US Locations:

Alabama

Arkansas

California

Montana

New jersey

North Carolina

Pennsylvania

South Dakota

Texas

U.S. Virgin Islands

Virginia Turquoise Crystals

Utah

Turquoise Structure

The formation of turquoise requires:

1. Aluminum, the third most common element in the earth's crust after oxygen and silicon

2. Phosphorus, the eleventh most common element

3. Copper, the twenty fifth most common element

and 4. Hot acid to dissolve and re-deposit it as a secondary mineral.

Add a little iron and you get Variquoise.

Add a little zinc and you get Faustite

Remove copper and you get Variscite.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turquoise

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminum, with the chemical formula CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O. It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone and ornamental stone for thousands of years owing to its unique hue. In recent times, turquoise has been devalued, like most other opaque gems, by the introduction onto the market of treatments, imitations and synthetics.

The gemstone has been known by many names. Pliny the Elder referred to the mineral as callais (from Ancient Greek κάλαϊς) and the Aztecs knew it as chalchihuitl.[4] The word turquoise dates to the 17th century and is derived from the French turquois for "Turkish" because the mineral was first brought to Europe through Turkey, from mines in the historical Khorasan Province of Persia.[2][3][4][5]

Properties

The finest of turquoise reaches a maximum Mohs hardness of just under 6, or slightly more than window glass.[2] Characteristically a cryptocrystalline mineral, turquoise almost never forms single crystals, and all of its properties are highly variable. X-ray diffraction testing shows its crystal system to be triclinic.[3][6] With lower hardness comes lower specific gravity (2.60–2.90)[3] and greater porosity; these properties are dependent on grain size. The lustre of turquoise is typically waxy to subvitreous, and its transparency is usually opaque, but may be semitranslucent in thin sections. Colour is as variable as the mineral's other properties, ranging from white to a powder blue to a sky blue, and from a blue-green to a yellowish green. The blue is attributed to idiochromatic copper while the green may be the result of either iron impurities (replacing aluminium) or dehydration.

The refractive index of turquoise (as measured by sodium light, 589.3 nm) is approximately 1.61 or 1.62; this is a mean value seen as a single reading on a gemological refractometer, owing to the almost invariably polycrystalline nature of turquoise. A reading of 1.61–1.65 (birefringence 0.040, biaxial positive) has been taken from rare single crystals. An absorption spectrum may also be obtained with a hand-held spectroscope, revealing a line at 432 nm and a weak band at 460 nm (this is best seen with strong reflected light). Under longwave ultraviolet light, turquoise may occasionally fluoresce green, yellow or bright blue; it is inert under shortwave ultraviolet and X-rays.

Turquoise is insoluble in all but heated hydrochloric acid. Its streak is a pale bluish white and its fracture is conchoidal,[3] leaving a waxy lustre. Despite its low hardness relative to other gems, turquoise takes a good polish. Turquoise may also be peppered with flecks of pyrite or interspersed with dark, spidery limonite veining.

Formation

"Big Blue", a large turquoise specimen from the copper mine at Cananea, Sonora, Mexico

As a secondary mineral, turquoise forms by the action of percolating acidic aqueous solutions during the weathering and oxidation of preexisting minerals. For example, the copper may come from primary copper sulfides such as chalcopyrite or from the secondary carbonates malachite or azurite; the aluminium may derive from feldspar; and the phosphorus from apatite. Climate factors appear to play an important role as turquoise is typically found in arid regions, filling or encrusting cavities and fractures in typically highly altered volcanic rocks, often with associated limonite and other iron oxides. In the Southwestern United States turquoise is almost invariably associated with the weathering products of copper sulfide deposits in or around potassium-feldspar-bearing porphyritic intrusives. In some occurrences alunite, potassium aluminium sulfate, is a prominent secondary mineral. Typically turquoise mineralization is restricted to a relatively shallow depth of less than 20 metres (66 feet), although it does occur along deeper fracture zones where secondary solutions have greater penetration or the depth to the water table is greater.

Turquoise is nearly always cryptocrystalline and massive and assumes no definite external shape. Crystals, even at the microscopic scale, are exceedingly rare. Typically the form is vein or fracture filling, nodular, or botryoidal in habit. Stalactite forms have been reported. Turquoise may also pseudomorphously replace feldspar, apatite, other minerals, or even fossils. Odontolite is fossil bone or ivory that has been traditionally thought to have been altered by turquoise or similar phosphate minerals such as the iron phosphate vivianite. Intergrowth with other secondary copper minerals such as chrysocolla is also common.

Occurrence

Massive Kingman blue turquoise in matrix with quartz from Mineral Park, Arizona, US

Turquoise was among the first gems to be mined, and many historic sites have been depleted, though some are still worked to this day. These are all small-scale operations, often seasonal owing to the limited scope and remoteness of the deposits. Most are worked by hand with little or no mechanization. However, turquoise is often recovered as a byproduct of large-scale copper mining operations, especially in the United States.

Cutting and grinding turquoise in Nishapur, Iran, 1973

Iran

Iran has been an important source of turquoise for at least 2,000 years. It was initially named by Iranians "pērōzah" meaning "victory", and later the Arabs called it "fayrūzah", which is pronounced in Modern Persian as "fīrūzeh". In Iranian architecture, the blue turquoise was used to cover the domes of palaces because its intense blue colour was also a symbol of heaven on earth.[citation needed]

Persian turquoise from Iran

This deposit is blue naturally and turns green when heated due to dehydration. It is restricted to a mine-riddled region in Nishapur, the 2,012 m (6,601 ft) mountain peak of Ali-mersai near Mashhad, the capital of Khorasan Province, Iran. A weathered and broken trachyte is host to the turquoise, which is found both in situ between layers of limonite and sandstone and amongst the scree at the mountain's base. These workings are the oldest known, together with those of the Sinai Peninsula.[5] Iran also has turquoise mines in Semnan and Kerman provinces.

Sinai

Since at least the First Dynasty (3000 BCE) in ancient Egypt, and possibly before then, turquoise was used by the Egyptians and was mined by them in the Sinai Peninsula. This region was known as the Country of Turquoise by the native Monitu. There are six mines in the peninsula, all on its southwest coast, covering an area of some 650 km2 (250 sq mi). The two most important of these mines, from a historic perspective, are Serabit el-Khadim and Wadi Maghareh, believed to be among the oldest of known mines. The former mine is situated about 4 kilometres from an ancient temple dedicated to the deity Hathor.

The turquoise is found in sandstone that is, or was originally, overlain by basalt. Copper and iron workings are present in the area. Large-scale turquoise mining is not profitable today, but the deposits are sporadically quarried by Bedouin peoples using homemade gunpowder.[citation needed] In the rainy winter months, miners face a risk from flash flooding; even in the dry season, death from the collapse of the haphazardly exploited sandstone mine walls is not unheard of. The colour of Sinai material is typically greener than Iranian material, but is thought to be stable and fairly durable. Often referred to as "Egyptian turquoise", Sinai material is typically the most translucent, and under magnification its surface structure is revealed to be peppered with dark blue discs not seen in material from other localities.

A selection of Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) turquoise and orange argillite inlay pieces from Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, US (dated c. 1020–1140) show the typical colour range and mottling of American turquoise. Some likely came from Los Cerrillos.

United States

A fine turquoise specimen from Los Cerrillos, New Mexico, US, at the Smithsonian Museum. Cerrillos turquoise was widely used by Native Americans prior to the Spanish conquest.

Bisbee turquoise commonly has a hard chocolate brown coloured matrix.

Untreated turquoise, Nevada, US. Rough nuggets from the McGinness Mine, Austin. Blue and green cabochons showing spiderweb, Bunker Hill Mine, Royston

The Southwest United States is a significant source of turquoise; Arizona, California (San Bernardino, Imperial, Inyo counties), Colorado (Conejos, El Paso, Lake, Saguache counties), New Mexico (Eddy, Grant, Otero, Santa Fe counties) and Nevada (Clark, Elko, Esmeralda County, Eureka, Lander, Mineral County and Nye counties) are (or were) especially rich. The deposits of California and New Mexico were mined by pre-Columbian Native Americans using stone tools, some local and some from as far away as central Mexico. Cerrillos, New Mexico is thought to be the location of the oldest mines; prior to the 1920s, the state was the country's largest producer; it is more or less exhausted today. Only one mine in California, located at Apache Canyon, operates at a commercial capacity today.

The turquoise occurs as vein or seam fillings, and as compact nuggets; these are mostly small in size. While quite fine material is sometimes found, rivalling Iranian material in both colour and durability, most American turquoise is of a low grade (called "chalk turquoise"); high iron levels mean greens and yellows predominate, and a typically friable consistency in the turquoise's untreated state precludes use in jewellery.

Arizona is currently the most important producer of turquoise by value.[5] Several mines exist in the state, two of them famous for their unique colour and quality and considered the best in the industry: the Sleeping Beauty Mine in Globe ceased turquoise mining in August 2012. The mine chose to send all ore to the crusher and to concentrate on copper production due to the rising price of copper on the world market. The price of natural untreated Sleeping Beauty turquoise has risen dramatically since the mine's closing. The Kingman Mine as of 2015 still operates alongside a copper mine outside of the city. Other mines include the Blue Bird mine, Castle Dome, and Ithaca Peak, but they are mostly inactive due to the high cost of operations and federal regulations The Phelps Dodge Lavender Pit mine at Bisbee ceased operations in 1974 and never had a turquoise contractor. All Bisbee turquoise was "lunch pail" mined. It came out of the copper ore mine in miners' lunch pails. Morenci and Turquoise Peak are either inactive or depleted.

Nevada is the country's other major producer, with more than 120 mines which have yielded significant quantities of turquoise. Unlike elsewhere in the US, most Nevada mines have been worked primarily for their gem turquoise and very little has been recovered as a byproduct of other mining operations. Nevada turquoise is found as nuggets, fracture fillings and in breccias as the cement filling interstices between fragments. Because of the geology of the Nevada deposits, a majority of the material produced is hard and dense, being of sufficient quality that no treatment or enhancement is required. While nearly every county in the state has yielded some turquoise, the chief producers are in Lander and Esmeralda counties. Most of the turquoise deposits in Nevada occur along a wide belt of tectonic activity that coincides with the state's zone of thrust faulting. It strikes about N15°E and extends from the northern part of Elko County, southward down to the California border southwest of Tonopah. Nevada has produced a wide diversity of colours and mixes of different matrix patterns, with turquoise from Nevada coming in various shades of blue, blue-green, and green. Some of this unusually coloured turquoise may contain significant zinc and iron, which is the cause of the beautiful bright green to yellow-green shades. Some of the green to green yellow shades may actually be variscite or faustite, which are secondary phosphate minerals similar in appearance to turquoise. A significant portion of the Nevada material is also noted for its often attractive brown or black limonite veining, producing what is called "spiderweb matrix". While a number of the Nevada deposits were first worked by Native Americans, the total Nevada turquoise production since the 1870s has been estimated at more than 600 tons, including nearly 400 tons from the Carico Lake mine. In spite of increased costs, small scale mining operations continue at a number of turquoise properties in Nevada, including the Godber, Orvil Jack and Carico Lake mines in Lander County, the Pilot Mountain Mine in Mineral County, and several properties in the Royston and Candelaria areas of Esmerelda County.[7]

In 1912, the first deposit of distinct, single-crystal turquoise was discovered in Lynch Station, Campbell County, Virginia. The crystals, forming a druse over the mother rock, are very small; 1 mm (0.04 in) is considered large. Until the 1980s Virginia was widely thought to be the only source of distinct crystals; there are now at least 27 other localities.[citation needed]

In an attempt to recoup profits and meet demand, some American turquoise is treated or enhanced to a certain degree. These treatments include innocuous waxing and more controversial procedures, such as dyeing and impregnation (see Treatments). There are however, some American mines which produce materials of high enough quality that no treatment or alterations are required. Any such treatments which have been performed should be disclosed to the buyer on sale of the material.

Other sources

Turquoise prehistoric artefacts (beads) are known since the fifth millennium BCE from sites in the Eastern Rhodopes in Bulgaria - the source for the raw material is possibly related to the nearby Spahievo Ph-Zn ore field.[8]

China has been a minor source of turquoise for 3,000 years or more. Gem-quality material, in the form of compact nodules, is found in the fractured, silicified limestone of Yunxian and Zhushan, Hubei province. Additionally, Marco Polo reported turquoise found in present-day Sichuan. Most Chinese material is exported, but a few carvings worked in a manner similar to jade exist. In Tibet, gem-quality deposits purportedly exist in the mountains of Derge and Nagari-Khorsum in the east and west of the region respectively.[9]

Other notable localities include: Afghanistan; Australia (Victoria and Queensland); north India; northern Chile (Chuquicamata); Cornwall; Saxony; Silesia; and Turkestan.

The gemstone has been known by many names. Pliny the Elder referred to the mineral as callais (from Ancient Greek κάλαϊς) and the Aztecs knew it as chalchihuitl.[4] The word turquoise dates to the 17th century and is derived from the French turquois for "Turkish" because the mineral was first brought to Europe through Turkey, from mines in the historical Khorasan Province of Persia.[2][3][4][5]

Properties

The finest of turquoise reaches a maximum Mohs hardness of just under 6, or slightly more than window glass.[2] Characteristically a cryptocrystalline mineral, turquoise almost never forms single crystals, and all of its properties are highly variable. X-ray diffraction testing shows its crystal system to be triclinic.[3][6] With lower hardness comes lower specific gravity (2.60–2.90)[3] and greater porosity; these properties are dependent on grain size. The lustre of turquoise is typically waxy to subvitreous, and its transparency is usually opaque, but may be semitranslucent in thin sections. Colour is as variable as the mineral's other properties, ranging from white to a powder blue to a sky blue, and from a blue-green to a yellowish green. The blue is attributed to idiochromatic copper while the green may be the result of either iron impurities (replacing aluminium) or dehydration.

The refractive index of turquoise (as measured by sodium light, 589.3 nm) is approximately 1.61 or 1.62; this is a mean value seen as a single reading on a gemological refractometer, owing to the almost invariably polycrystalline nature of turquoise. A reading of 1.61–1.65 (birefringence 0.040, biaxial positive) has been taken from rare single crystals. An absorption spectrum may also be obtained with a hand-held spectroscope, revealing a line at 432 nm and a weak band at 460 nm (this is best seen with strong reflected light). Under longwave ultraviolet light, turquoise may occasionally fluoresce green, yellow or bright blue; it is inert under shortwave ultraviolet and X-rays.

Turquoise is insoluble in all but heated hydrochloric acid. Its streak is a pale bluish white and its fracture is conchoidal,[3] leaving a waxy lustre. Despite its low hardness relative to other gems, turquoise takes a good polish. Turquoise may also be peppered with flecks of pyrite or interspersed with dark, spidery limonite veining.

Formation

"Big Blue", a large turquoise specimen from the copper mine at Cananea, Sonora, Mexico

As a secondary mineral, turquoise forms by the action of percolating acidic aqueous solutions during the weathering and oxidation of preexisting minerals. For example, the copper may come from primary copper sulfides such as chalcopyrite or from the secondary carbonates malachite or azurite; the aluminium may derive from feldspar; and the phosphorus from apatite. Climate factors appear to play an important role as turquoise is typically found in arid regions, filling or encrusting cavities and fractures in typically highly altered volcanic rocks, often with associated limonite and other iron oxides. In the Southwestern United States turquoise is almost invariably associated with the weathering products of copper sulfide deposits in or around potassium-feldspar-bearing porphyritic intrusives. In some occurrences alunite, potassium aluminium sulfate, is a prominent secondary mineral. Typically turquoise mineralization is restricted to a relatively shallow depth of less than 20 metres (66 feet), although it does occur along deeper fracture zones where secondary solutions have greater penetration or the depth to the water table is greater.

Turquoise is nearly always cryptocrystalline and massive and assumes no definite external shape. Crystals, even at the microscopic scale, are exceedingly rare. Typically the form is vein or fracture filling, nodular, or botryoidal in habit. Stalactite forms have been reported. Turquoise may also pseudomorphously replace feldspar, apatite, other minerals, or even fossils. Odontolite is fossil bone or ivory that has been traditionally thought to have been altered by turquoise or similar phosphate minerals such as the iron phosphate vivianite. Intergrowth with other secondary copper minerals such as chrysocolla is also common.

Occurrence

Massive Kingman blue turquoise in matrix with quartz from Mineral Park, Arizona, US

Turquoise was among the first gems to be mined, and many historic sites have been depleted, though some are still worked to this day. These are all small-scale operations, often seasonal owing to the limited scope and remoteness of the deposits. Most are worked by hand with little or no mechanization. However, turquoise is often recovered as a byproduct of large-scale copper mining operations, especially in the United States.

Cutting and grinding turquoise in Nishapur, Iran, 1973

Iran

Iran has been an important source of turquoise for at least 2,000 years. It was initially named by Iranians "pērōzah" meaning "victory", and later the Arabs called it "fayrūzah", which is pronounced in Modern Persian as "fīrūzeh". In Iranian architecture, the blue turquoise was used to cover the domes of palaces because its intense blue colour was also a symbol of heaven on earth.[citation needed]

Persian turquoise from Iran

This deposit is blue naturally and turns green when heated due to dehydration. It is restricted to a mine-riddled region in Nishapur, the 2,012 m (6,601 ft) mountain peak of Ali-mersai near Mashhad, the capital of Khorasan Province, Iran. A weathered and broken trachyte is host to the turquoise, which is found both in situ between layers of limonite and sandstone and amongst the scree at the mountain's base. These workings are the oldest known, together with those of the Sinai Peninsula.[5] Iran also has turquoise mines in Semnan and Kerman provinces.

Sinai

Since at least the First Dynasty (3000 BCE) in ancient Egypt, and possibly before then, turquoise was used by the Egyptians and was mined by them in the Sinai Peninsula. This region was known as the Country of Turquoise by the native Monitu. There are six mines in the peninsula, all on its southwest coast, covering an area of some 650 km2 (250 sq mi). The two most important of these mines, from a historic perspective, are Serabit el-Khadim and Wadi Maghareh, believed to be among the oldest of known mines. The former mine is situated about 4 kilometres from an ancient temple dedicated to the deity Hathor.

The turquoise is found in sandstone that is, or was originally, overlain by basalt. Copper and iron workings are present in the area. Large-scale turquoise mining is not profitable today, but the deposits are sporadically quarried by Bedouin peoples using homemade gunpowder.[citation needed] In the rainy winter months, miners face a risk from flash flooding; even in the dry season, death from the collapse of the haphazardly exploited sandstone mine walls is not unheard of. The colour of Sinai material is typically greener than Iranian material, but is thought to be stable and fairly durable. Often referred to as "Egyptian turquoise", Sinai material is typically the most translucent, and under magnification its surface structure is revealed to be peppered with dark blue discs not seen in material from other localities.

A selection of Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) turquoise and orange argillite inlay pieces from Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, US (dated c. 1020–1140) show the typical colour range and mottling of American turquoise. Some likely came from Los Cerrillos.

United States

A fine turquoise specimen from Los Cerrillos, New Mexico, US, at the Smithsonian Museum. Cerrillos turquoise was widely used by Native Americans prior to the Spanish conquest.

Bisbee turquoise commonly has a hard chocolate brown coloured matrix.

Untreated turquoise, Nevada, US. Rough nuggets from the McGinness Mine, Austin. Blue and green cabochons showing spiderweb, Bunker Hill Mine, Royston

The Southwest United States is a significant source of turquoise; Arizona, California (San Bernardino, Imperial, Inyo counties), Colorado (Conejos, El Paso, Lake, Saguache counties), New Mexico (Eddy, Grant, Otero, Santa Fe counties) and Nevada (Clark, Elko, Esmeralda County, Eureka, Lander, Mineral County and Nye counties) are (or were) especially rich. The deposits of California and New Mexico were mined by pre-Columbian Native Americans using stone tools, some local and some from as far away as central Mexico. Cerrillos, New Mexico is thought to be the location of the oldest mines; prior to the 1920s, the state was the country's largest producer; it is more or less exhausted today. Only one mine in California, located at Apache Canyon, operates at a commercial capacity today.

The turquoise occurs as vein or seam fillings, and as compact nuggets; these are mostly small in size. While quite fine material is sometimes found, rivalling Iranian material in both colour and durability, most American turquoise is of a low grade (called "chalk turquoise"); high iron levels mean greens and yellows predominate, and a typically friable consistency in the turquoise's untreated state precludes use in jewellery.

Arizona is currently the most important producer of turquoise by value.[5] Several mines exist in the state, two of them famous for their unique colour and quality and considered the best in the industry: the Sleeping Beauty Mine in Globe ceased turquoise mining in August 2012. The mine chose to send all ore to the crusher and to concentrate on copper production due to the rising price of copper on the world market. The price of natural untreated Sleeping Beauty turquoise has risen dramatically since the mine's closing. The Kingman Mine as of 2015 still operates alongside a copper mine outside of the city. Other mines include the Blue Bird mine, Castle Dome, and Ithaca Peak, but they are mostly inactive due to the high cost of operations and federal regulations The Phelps Dodge Lavender Pit mine at Bisbee ceased operations in 1974 and never had a turquoise contractor. All Bisbee turquoise was "lunch pail" mined. It came out of the copper ore mine in miners' lunch pails. Morenci and Turquoise Peak are either inactive or depleted.

Nevada is the country's other major producer, with more than 120 mines which have yielded significant quantities of turquoise. Unlike elsewhere in the US, most Nevada mines have been worked primarily for their gem turquoise and very little has been recovered as a byproduct of other mining operations. Nevada turquoise is found as nuggets, fracture fillings and in breccias as the cement filling interstices between fragments. Because of the geology of the Nevada deposits, a majority of the material produced is hard and dense, being of sufficient quality that no treatment or enhancement is required. While nearly every county in the state has yielded some turquoise, the chief producers are in Lander and Esmeralda counties. Most of the turquoise deposits in Nevada occur along a wide belt of tectonic activity that coincides with the state's zone of thrust faulting. It strikes about N15°E and extends from the northern part of Elko County, southward down to the California border southwest of Tonopah. Nevada has produced a wide diversity of colours and mixes of different matrix patterns, with turquoise from Nevada coming in various shades of blue, blue-green, and green. Some of this unusually coloured turquoise may contain significant zinc and iron, which is the cause of the beautiful bright green to yellow-green shades. Some of the green to green yellow shades may actually be variscite or faustite, which are secondary phosphate minerals similar in appearance to turquoise. A significant portion of the Nevada material is also noted for its often attractive brown or black limonite veining, producing what is called "spiderweb matrix". While a number of the Nevada deposits were first worked by Native Americans, the total Nevada turquoise production since the 1870s has been estimated at more than 600 tons, including nearly 400 tons from the Carico Lake mine. In spite of increased costs, small scale mining operations continue at a number of turquoise properties in Nevada, including the Godber, Orvil Jack and Carico Lake mines in Lander County, the Pilot Mountain Mine in Mineral County, and several properties in the Royston and Candelaria areas of Esmerelda County.[7]

In 1912, the first deposit of distinct, single-crystal turquoise was discovered in Lynch Station, Campbell County, Virginia. The crystals, forming a druse over the mother rock, are very small; 1 mm (0.04 in) is considered large. Until the 1980s Virginia was widely thought to be the only source of distinct crystals; there are now at least 27 other localities.[citation needed]

In an attempt to recoup profits and meet demand, some American turquoise is treated or enhanced to a certain degree. These treatments include innocuous waxing and more controversial procedures, such as dyeing and impregnation (see Treatments). There are however, some American mines which produce materials of high enough quality that no treatment or alterations are required. Any such treatments which have been performed should be disclosed to the buyer on sale of the material.

Other sources

Turquoise prehistoric artefacts (beads) are known since the fifth millennium BCE from sites in the Eastern Rhodopes in Bulgaria - the source for the raw material is possibly related to the nearby Spahievo Ph-Zn ore field.[8]

China has been a minor source of turquoise for 3,000 years or more. Gem-quality material, in the form of compact nodules, is found in the fractured, silicified limestone of Yunxian and Zhushan, Hubei province. Additionally, Marco Polo reported turquoise found in present-day Sichuan. Most Chinese material is exported, but a few carvings worked in a manner similar to jade exist. In Tibet, gem-quality deposits purportedly exist in the mountains of Derge and Nagari-Khorsum in the east and west of the region respectively.[9]

Other notable localities include: Afghanistan; Australia (Victoria and Queensland); north India; northern Chile (Chuquicamata); Cornwall; Saxony; Silesia; and Turkestan.

The most sought for color is Robin Egg Blue.

Two Excellent sites:

www.durangosilver.com/NevadaturqM.htm

The Four Major Turquoise Producing States are 1. Nevada, 2. Arizona, 3. new Mexico, and 4. Colorado.

handeyemagazine.com/content/american-turquoise-gemstone-southwest

handeyemagazine.com/content/american-turquoise-gemstone-southwest

According to Waddell, American turquoise production has drastically changed since he started in the business over forty years ago. “In the 1970s, 60 to 70 percent of the turquoise mines were still in production and now 95 percent are shut down,” he says. While New Mexico boasts of prehistoric mining, Nevada is the state that produced the most turquoise but Arizona is the only state left with commercially producing mines, Kingman and Sleeping Beauty. Many of the old mines have been depleted or it is just too expensive to continue the mining process.

The vast amount of turquoise used in medium and lesser expensive Indian jewelry today is imported from China. And since around 80 percent of the turquoise produced is soft and of inferior quality, it is often treated with dyes and resins creating ‘stabilized’ or ‘enhanced’ turquoise. ‘Natural turquoise’ indicates the stone has not been treated in any way.

The vast amount of turquoise used in medium and lesser expensive Indian jewelry today is imported from China. And since around 80 percent of the turquoise produced is soft and of inferior quality, it is often treated with dyes and resins creating ‘stabilized’ or ‘enhanced’ turquoise. ‘Natural turquoise’ indicates the stone has not been treated in any way.

Bisbee Turquoise

Bisbee Turquoise Castle Dome Later Called Pinto Valley

Castle Dome Later Called Pinto Valley Cave Creek

Cave Creek Ithaca Peak

Ithaca Peak Kingman

Kingman Morenci

Morenci Sleeping Beauty

Sleeping Beauty Turquoise Mountain and "Birdseye"

Turquoise Mountain and "Birdseye"

This view of the pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico in the late 1800's gives a fairly accurate idea of the appearance of Hawiku, on its low hill, when the Coronado army attacked in July, 1540.

This view of the pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico in the late 1800's gives a fairly accurate idea of the appearance of Hawiku, on its low hill, when the Coronado army attacked in July, 1540.

Villa Grove

Villa Grove