Post by 1dave on Oct 20, 2021 22:11:17 GMT -5

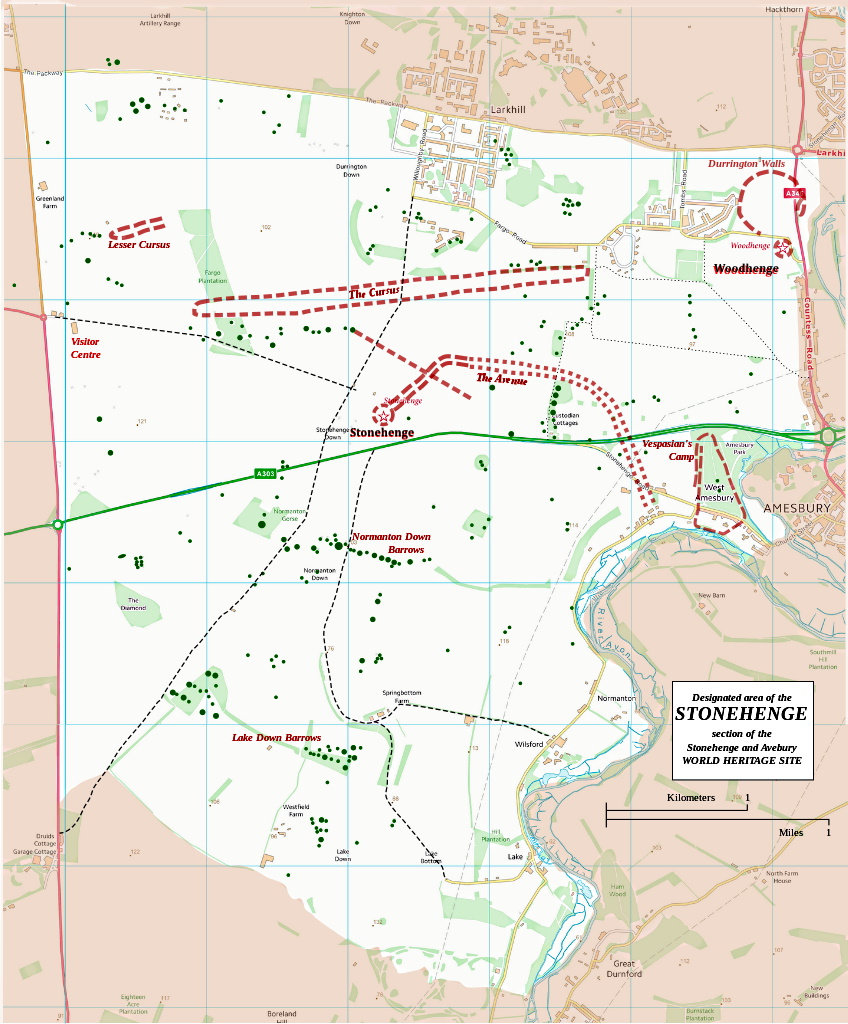

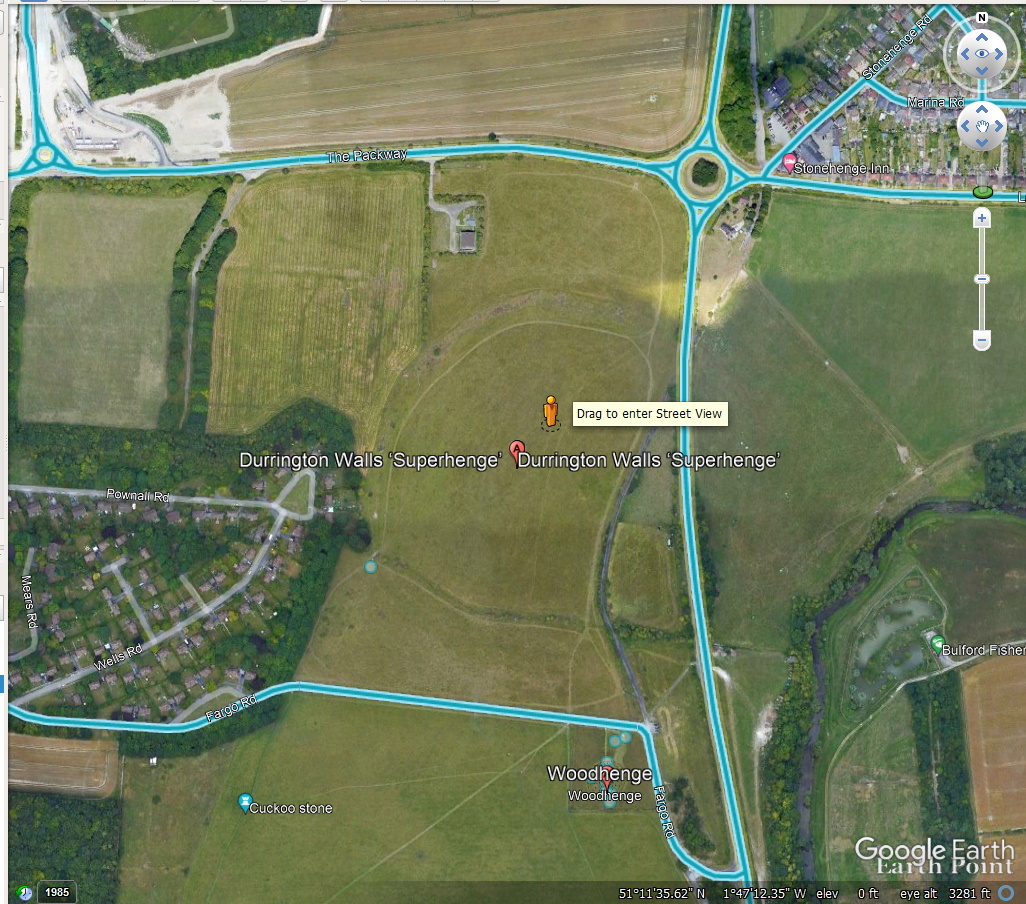

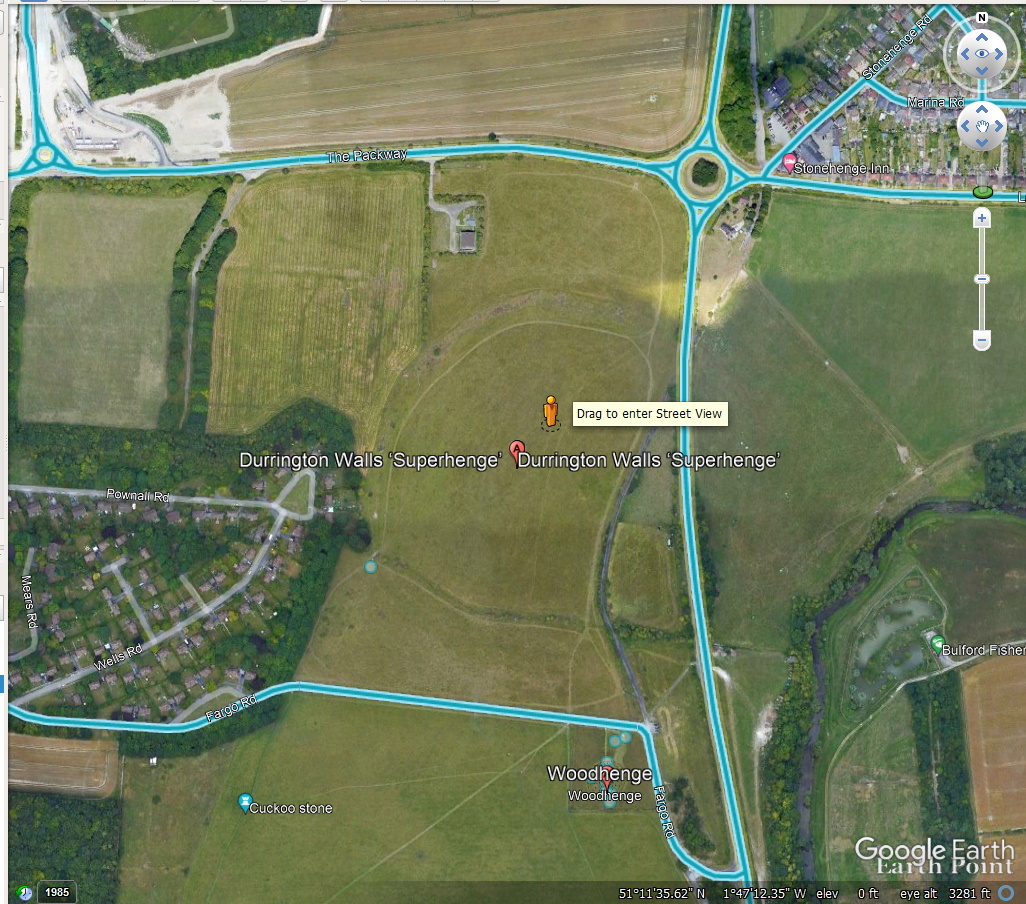

In the upper right corner . . .

Woodhenge

"Superhenge"

archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/rethinking-durrington-walls-a-long-lost-monument-revealed.htm

Rethinking Durrington Walls: a long-lost monument revealed

October 10, 2016

23 mins read

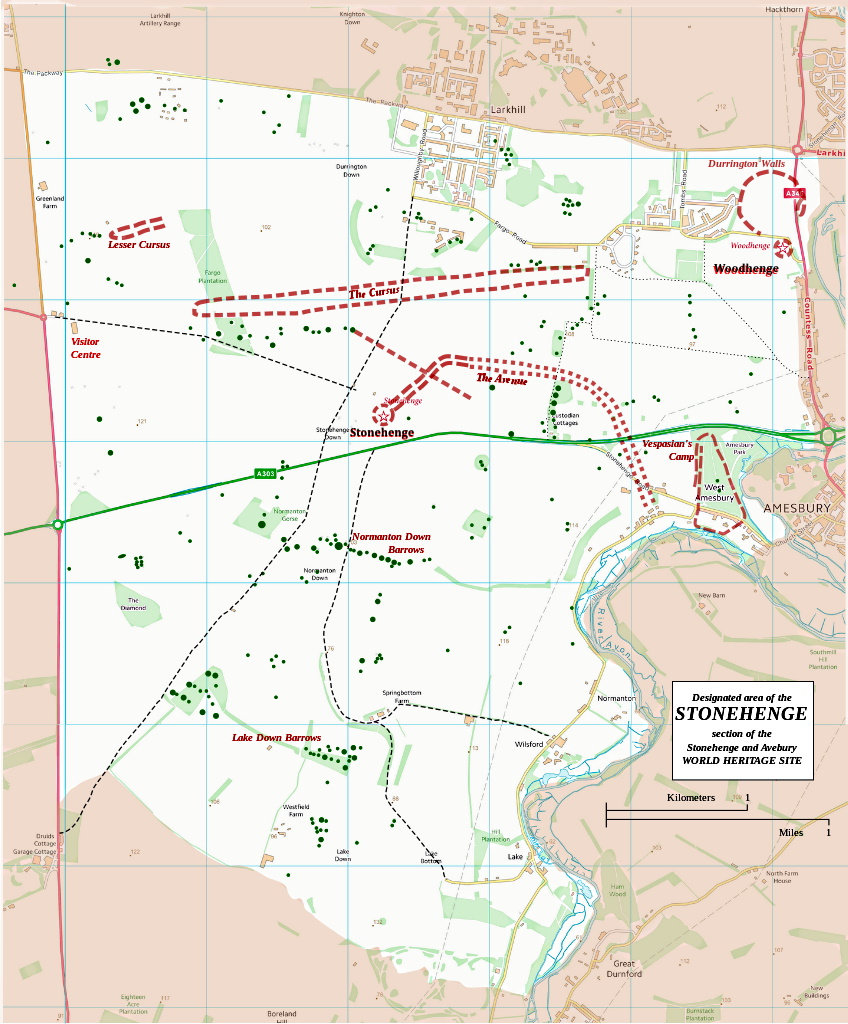

Durrington Walls, two miles from Stonehenge, is named after the Neolithic henge that calls the location home. But with ongoing research revealing a massive and previously unknown monument hidden beneath its banks, the site’s history is set to be rewritten. Carly Hilts spoke to Vince Gaffney, Mike Parker Pearson, and Nick Snashall to find out more.

monument-landscape

Around 4,500 years ago, hundreds of people gathered two miles from Stonehenge to build another massive monument, at a location known to us as Durrington Walls. The spot they had selected lay within sight of the celebrated stones, and had previously been home to a village that may have housed the community that erected them (CA 208). But now the short-lived settlement lay abandoned, and – perhaps motivated by a desire to commemorate its presence – the new group of builders punched through the living surfaces and midden material of their predecessors to complete their work.

Their efforts were not focused on raising the imposing earthworks of the henge that gives the site its modern name, however. Instead, their labour created a previously unknown earlier phase whose full extent is only now being revealed by ongoing research: as many as 300 huge wooden posts, evenly spaced 5m apart in a ring almost 450m across. It would have been an arresting sight, yet within a maximum of 50 years the monument had been decommissioned once more, its posts removed and their sockets filled in, before being covered over by the henge that we see today. All trace of the post circle would lie hidden beneath the banks of its successor for millennia – until it was brought to light once more by a series of excavations and the largest geophysical survey of its kind. Why did the site undergo such a sudden change in design, and what can we learn about the rise and fall of a long-lost monument? As analysis continues, intriguing clues are beginning to emerge.

. . .

. . .

Durrington decommissioned

Despite this apparent haste, however, this was no wanton destruction. The pits and ramps show no sign of the damage that might be expected if the posts had simply been hauled over sideways and dragged from their sockets. On the contrary, concentric rings at the bottom of one of the excavated postholes suggest that the timbers had been carefully twisted loose before being extracted vertically. Was this a sign of respect for a significant site at the end of its life? Or might the decommissioners instead have been salvaging the posts for reuse elsewhere?

Such suggestions can only be speculative, but tantalising clues to just such a process might possibly lie nearby. In 1967, Geoffrey Wainwright led the excavation of two rather different prehistoric post arrangements, formed of multiple concentric rings of timbers, just 200m from Durrington Walls. The larger of these, known as the Southern Timber Circle, seems to have undergone significant augmentation at the very same time that the Durrington Walls palisaded enclosure was being taken apart – modifications that included the addition of 200 new posts. Might this have been the final home of the Durrington timbers?

It is a tempting possibility – though, as an alternative, Mike also proposes a more prosaic fate: when the enclosure was dismantled, the builders were probably already planning to build the henge that so swiftly replaced it, a project that required a vertically sided ditch some 6m deep. ‘This would have been tricky to get into,’ he said. ‘I wonder if some of the timbers might have been turned into notched log ladders of the type we have seen elsewhere for this period – they would have been perfect for that.’

Whether the timbers’ next use was ceremonial or more mundane, and wherever they ended up, their departure from Durrington Walls was marked by the Neolithic community. All of the empty postholes were packed with quantities of chalk fragments: it was this densely crammed rubble that had produced signals during the geophysical survey, which led the team to interpret the remains as standing stones. Furthermore, the route of the new henge was designed to follow the line of the pits.

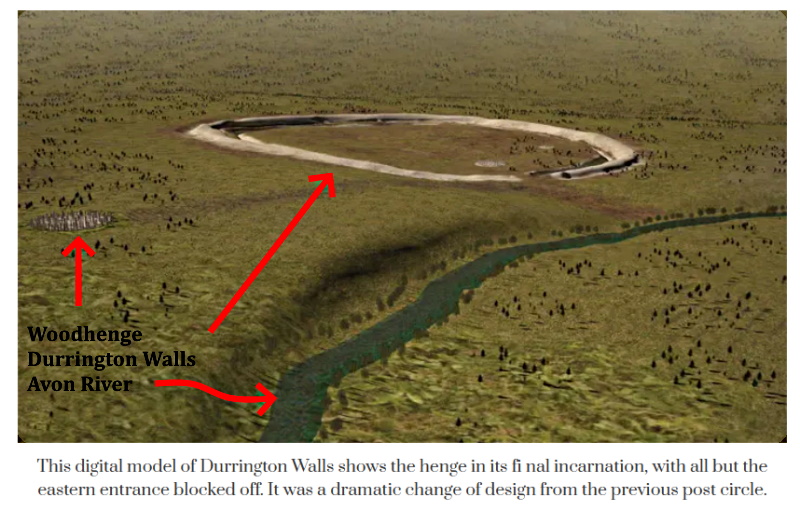

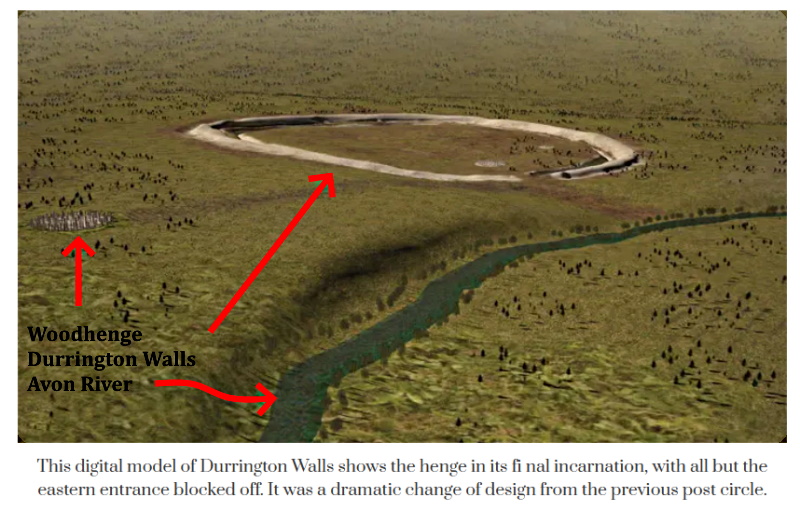

The henge was a dramatic break with the earlier design of the site: a 3m-high circular bank accompanied by a ditch 3-5m wide. But what prompted this radical change of direction, and so soon after the post circle was built? Could this simply be attributed to the mercurial moods of senior management that we are all so familiar with today – a vivid illustration of the people and resources that the prehistoric elite could command? Or could the change have been more dramatic?

Such a major switch might hint at a change in the social order and a particular group or individual wanting to impose their own stamp on the landscape, suggests Nick Snashall, National Trust archaeologist for the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site: ‘It is possible that the breaking up of the diverse group of people who had come from across Britain to build Stonehenge may have created social instability,’ she said. ‘This is a moment of such change that you almost feel that someone new had taken sway.’

While the care apparently given to dismantling the palisaded enclosure suggests that this was not a violent change, Vince Gaffney of Bradford University, who co-directed the geophysical work, agrees that there may have been an ideological motive behind it. ‘I think theological change seems reasonable, given the scale and speed of the transformation,’ he said.

Prehistoric prestige?

Instead of a destructive change, might we be better off viewing the creation of the henge as an upgrade to the site? Given that the Durrington palisaded enclosure falls quite late in the tradition of such monuments, ideas of some kind of prehistoric Reformation might be misplaced, Mike suggests.

‘Yes, the palisaded enclosure would have been a big undertaking, but its creation represents a tiny amount of effort compared to building a henge bank and ditch with antler picks – that is a project that would have required not hundreds but thousands of people.’

For prehistoric monuments to have undergone striking redesigns is not unknown on Salisbury Plain; after all, the layout of the stones of Stonehenge shifted multiple times during its life (CA 275), while Avebury’s avenue was relatively late in joining the rest of the Neolithic complex. Nor would the arrival of the henge be the last modification of Durrington Walls: at some point two or three centuries later, its north and south entrances were blocked off and their causeways severed to create the continuous bank with a single eastern entrance that we see today.

As for the future, the team has no immediate plans to excavate any more of the pits, but the site and its surroundings may yet yield further secrets. The vast datasets of geophysical survey results produced by the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project will take time to sift through, and the next step will be to work through these and continue to refine their results. The Stonehenge landscape has been studied in varying degrees of detail by generations of archaeologists and antiquarians, but new technology may hold the key to eking out even more previously unknown features. As Vince Gaffney comments: ‘It’s a site that keeps on giving.’

Woodhenge

"Superhenge"

archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/rethinking-durrington-walls-a-long-lost-monument-revealed.htm

Rethinking Durrington Walls: a long-lost monument revealed

October 10, 2016

23 mins read

Durrington Walls, two miles from Stonehenge, is named after the Neolithic henge that calls the location home. But with ongoing research revealing a massive and previously unknown monument hidden beneath its banks, the site’s history is set to be rewritten. Carly Hilts spoke to Vince Gaffney, Mike Parker Pearson, and Nick Snashall to find out more.

monument-landscape

Around 4,500 years ago, hundreds of people gathered two miles from Stonehenge to build another massive monument, at a location known to us as Durrington Walls. The spot they had selected lay within sight of the celebrated stones, and had previously been home to a village that may have housed the community that erected them (CA 208). But now the short-lived settlement lay abandoned, and – perhaps motivated by a desire to commemorate its presence – the new group of builders punched through the living surfaces and midden material of their predecessors to complete their work.

Their efforts were not focused on raising the imposing earthworks of the henge that gives the site its modern name, however. Instead, their labour created a previously unknown earlier phase whose full extent is only now being revealed by ongoing research: as many as 300 huge wooden posts, evenly spaced 5m apart in a ring almost 450m across. It would have been an arresting sight, yet within a maximum of 50 years the monument had been decommissioned once more, its posts removed and their sockets filled in, before being covered over by the henge that we see today. All trace of the post circle would lie hidden beneath the banks of its successor for millennia – until it was brought to light once more by a series of excavations and the largest geophysical survey of its kind. Why did the site undergo such a sudden change in design, and what can we learn about the rise and fall of a long-lost monument? As analysis continues, intriguing clues are beginning to emerge.

. . .

. . .

Durrington decommissioned

Despite this apparent haste, however, this was no wanton destruction. The pits and ramps show no sign of the damage that might be expected if the posts had simply been hauled over sideways and dragged from their sockets. On the contrary, concentric rings at the bottom of one of the excavated postholes suggest that the timbers had been carefully twisted loose before being extracted vertically. Was this a sign of respect for a significant site at the end of its life? Or might the decommissioners instead have been salvaging the posts for reuse elsewhere?

Such suggestions can only be speculative, but tantalising clues to just such a process might possibly lie nearby. In 1967, Geoffrey Wainwright led the excavation of two rather different prehistoric post arrangements, formed of multiple concentric rings of timbers, just 200m from Durrington Walls. The larger of these, known as the Southern Timber Circle, seems to have undergone significant augmentation at the very same time that the Durrington Walls palisaded enclosure was being taken apart – modifications that included the addition of 200 new posts. Might this have been the final home of the Durrington timbers?

It is a tempting possibility – though, as an alternative, Mike also proposes a more prosaic fate: when the enclosure was dismantled, the builders were probably already planning to build the henge that so swiftly replaced it, a project that required a vertically sided ditch some 6m deep. ‘This would have been tricky to get into,’ he said. ‘I wonder if some of the timbers might have been turned into notched log ladders of the type we have seen elsewhere for this period – they would have been perfect for that.’

Whether the timbers’ next use was ceremonial or more mundane, and wherever they ended up, their departure from Durrington Walls was marked by the Neolithic community. All of the empty postholes were packed with quantities of chalk fragments: it was this densely crammed rubble that had produced signals during the geophysical survey, which led the team to interpret the remains as standing stones. Furthermore, the route of the new henge was designed to follow the line of the pits.

The henge was a dramatic break with the earlier design of the site: a 3m-high circular bank accompanied by a ditch 3-5m wide. But what prompted this radical change of direction, and so soon after the post circle was built? Could this simply be attributed to the mercurial moods of senior management that we are all so familiar with today – a vivid illustration of the people and resources that the prehistoric elite could command? Or could the change have been more dramatic?

Such a major switch might hint at a change in the social order and a particular group or individual wanting to impose their own stamp on the landscape, suggests Nick Snashall, National Trust archaeologist for the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site: ‘It is possible that the breaking up of the diverse group of people who had come from across Britain to build Stonehenge may have created social instability,’ she said. ‘This is a moment of such change that you almost feel that someone new had taken sway.’

While the care apparently given to dismantling the palisaded enclosure suggests that this was not a violent change, Vince Gaffney of Bradford University, who co-directed the geophysical work, agrees that there may have been an ideological motive behind it. ‘I think theological change seems reasonable, given the scale and speed of the transformation,’ he said.

Prehistoric prestige?

Instead of a destructive change, might we be better off viewing the creation of the henge as an upgrade to the site? Given that the Durrington palisaded enclosure falls quite late in the tradition of such monuments, ideas of some kind of prehistoric Reformation might be misplaced, Mike suggests.

‘Yes, the palisaded enclosure would have been a big undertaking, but its creation represents a tiny amount of effort compared to building a henge bank and ditch with antler picks – that is a project that would have required not hundreds but thousands of people.’

For prehistoric monuments to have undergone striking redesigns is not unknown on Salisbury Plain; after all, the layout of the stones of Stonehenge shifted multiple times during its life (CA 275), while Avebury’s avenue was relatively late in joining the rest of the Neolithic complex. Nor would the arrival of the henge be the last modification of Durrington Walls: at some point two or three centuries later, its north and south entrances were blocked off and their causeways severed to create the continuous bank with a single eastern entrance that we see today.

As for the future, the team has no immediate plans to excavate any more of the pits, but the site and its surroundings may yet yield further secrets. The vast datasets of geophysical survey results produced by the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project will take time to sift through, and the next step will be to work through these and continue to refine their results. The Stonehenge landscape has been studied in varying degrees of detail by generations of archaeologists and antiquarians, but new technology may hold the key to eking out even more previously unknown features. As Vince Gaffney comments: ‘It’s a site that keeps on giving.’

You're down here in the bilges with the wharf rats. You will get more mileage above on the upper decks.

You're down here in the bilges with the wharf rats. You will get more mileage above on the upper decks.